Histopathological Pattern of Endometrial Hyperplasia in Peri- and Postmenopausal Women

*Fardousi F,1 Sultana SS,2 Kaizer N,3 Dewan RK,4 Jinnah MS,5 Jeba R,6 Hoque MN,7 Hussain M8

Abstract

Endometrial hyperplasia is one of the major gynaecological problem in peri- and post-menopausal women worldwide. It deserves special attention because of its relationship with endometrial carcinoma. The histopathological pattern of endometrial hyperplasia in peri- and post-menopausal women and their relationship with clinicopathological features are imperative to reach a diagnosis as well as early management. To find out the histopathological patterns of endometrial hyperplasia in peri- and post-menopausal women this descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out at the Department of Pathology, Dhaka Medical College, Dhaka during the period from January 2013 to December 2014. A total of seventy histopathologically diagnosed cases of endometrial hyperplasia were included in this study according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Among the 70 cases, endometrial curettage biopsy specimens were 45 and hysterectomy specimens were 25. Routine Haematoxylin & Eosin staining was done on all cases. Out of all endometrial hyperplasia cases, 53 cases were simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia, 8 cases were simple endometrial hyperplasia with atypia, 6 cases were complex endometrial hyperplasia without atypia and 3 cases were complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia. Majority of the patients 35 (50%) were between 41-50 years of age. The study revealed that most common histopathological pattern of endometrial hyperplasia was simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia, followed by simple endometrial hyperplasia with atypia. The importance of knowledge about the histological pattern of endometrium in abnormal uterine bleeding in different age group is useful in managing the cases with accuracy.

[Journal of Histopathology and Cytopathology, 2018 Jan; 2 (1):30-40]

Key words: Endometrial hyperplasia, gynecological problem, peri- and postmenopausal women, histopathological pattern.

- *Dr. Farzana Fardousi, Lecturer, Department of Cytopathology, National Institute of Cancer Research and Hospital (NICRH), Mohakhali, Dhaka. farzanafardousi@yahoo.com

- SK Salowa Sultana, Assistant Professor, Department of Pathology, Ad Din Women’s Medical College.Dhaka

- Nahid Kaizer, Associate Professor (CC), Department of Pathology, Shahabuddin Medical College. Dhaka

- Professor Dr. Rezaul Karim Dewan, Head of the Department of Pathology, Dhaka Medical College.

- Mohammed Shahed Ali Jinnah, Associate Professor, Department of Pathology, Dhaka Medical College.

- Ruksana Jeba, Associate Professor Department of Pathology, Dhaka Medical College.

- Md. Nazmul Hoque, Ex Associate Professor, Department of Pathology, Dhaka Medical College

- Professor Dr. Maleeha Hussain , Ex Head of the Department of Pathology, Dhaka Medical College.

*For correspondence

Introduction

Endometrial hyperplasia is defined as an increased proliferation of the endometrial glands relative to the stroma, resulting in an increased gland-to-stroma ratio when compared with normal proliferative endometrium. Endometrial hyperplasia deserves special attention because of its relationship with endometrial carcinoma in peri and postmenopausal women.1 Worldwide, endometrial cancer is the most common invasive cancer of female genital tract.

In 50% cases of endometrial adenocarcinoma, endometrial hyperplasia particularly atypical hyperplasia is found as a premalignant lesion.2 Endometrial hyperplasia usually develops in the presence of continuous estrogen stimulation unopposed by progesterone. In the years before menopause, women may have numerous cycles without ovulation (anovulatory) during which there is continuous unopposed estrogen activity. Similarly, hormone replacement therapy consisting of estrogen without progesterone may lead to endometrial hyperplasia.3 The endometrium becomes atrophic after menopause as a result of ovarian failure. The postmenopausal endometrium which despite being atrophic, retain a weak proliferative pattern for many years probably as a response to continuous low level of estrogenic stimulation. These are at a higher risk of progression to endometrial hyperplasia and subsequently to endometrial malignancy.3 Many classifications of endometrial hyperplasia have been proposed over the years. The one that is currently preferred and which has been recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) was originally proposed.4 It takes into account both the architectural and cytologic features, for reasons of dividing the hyperplasias into simple and complex based on architecture and subdividing each into typical and atypical on the basis of their cytological pattern.5 The type I endometrial cancers which is endometrioid variant is associated with unopposed estrogen exposure and is often preceded by atypical endometrial hyperplasia. However, type II endometrial cancers where a non-endometrioid histology (usually papillary, serous or clear cell) has an aggressive clinical course, is not preceded by any type of endometrial hyperplasia.6 According to WHO, endometrial hyperplasia is divided into four major categories: Simple hyperplasia without atypia, Simple hyperplasia with atypia, Complex hyperplasia without atypia and Complex hyperplasia with atypia. The confirmed diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia can be made by histopathological examination.7 Endometrial hyperplasia is associated with prolonged estrogen stimulation of the endometrium, which can be due to anovulation, increased estrogen production from endogenous sources or exogenous estrogen. The factors associated with endometrial hyperplasia include obesity, menopause, polycystic ovarian diseases, functioning granulosa cell tumors of the ovary, excessive cortical function and prolonged administration of estrogenic substances.1 The primary presenting symptom of endometrial hyperplasia is abnormal uterine bleeding, which typically prompts an endometrial biopsy to rule out carcinoma.8 Approximately, 70% of women with abnormal uterine bleeding are diagnosed with benign findings and 15% are diagnosed with carcinoma. The remaining 15% receive a diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia, which includes a broad range of lesions, from mild, reversible proliferations to the immediate precursors of carcinoma. Abnormal uterine bleeding is the chief complaints of endometrial hyperplasia and can be categorized into dysfunctional uterine bleeding or postmenopausal bleeding. Long reproductive life has risk for development of endometrial hyperplasia. Different studies have shown that, women who have achieved early menarche or late menopause have more risk for development of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial carcinoma, as estrogen exposure especially unopposed by progesterone is a known risk factor for the development of endometrial carcinoma. Parity causes estrogen-hormonal environment throughout the fertile years of a woman, which may increase risk for the development of endometrial carcinoma.9 Obesity is a known risk factor for endometrial hyperplasia and this excess risk is associated with the endocrine and inflammatory effects of adipose tissue. Adipocytes express aromatase that converts ovarian androgens into estrogens, which induce endometrial proliferation.10 It was observed in different studies that, endometrial hyperplasia was found in diabetic and hypertensive patient, but whether this association is statistically significant or not or whether it carries a risk of endometrial carcinoma for diabetic and hypertensive women need to be ascertained with further studies in a larger series of population. It was observed in many studies that endometrial hyperplasia is associated with family history of endometrial cancer. Because a common genetic alteration found in a significant number of endometrial hyperplasias and related endometrial carcinomas i.e. inactivation of the PTEN tumour suppressor gene.11 The study was aimed to find out the histopathological patterns of endometrial hyperplasia in peri- and post-menopausal women.

Methods

Place and period of study

This is a descriptive cross-sectional study which was carried out at the Department of Pathology, Dhaka Medical College, Dhaka, during the period of January 2013 to December 2014.

Sample Size

For this study, 110 peri- and postmenopausal women with dysfunctional uterine bleeding or postmenopausal bleeding who underwent D&C or hysterectomy were screened. A total of seventy histopathologically diagnosed cases of endometrial hyperplasia who met the enrollment criteria (inclusion & exclusion criteria) were included in this study. Among 70 cases, endometrial curettage biopsy specimens were 45 and hysterectomy specimens were 25. Routine Haematoxylin & Eosin staining was done on all cases.

Collection of Sample

Ethical clearance was taken for this study from institutional ethical committee of Dhaka Medical College, Dhaka. Each patient was interviewed before collection of the specimen and relevant information was recorded in a prescribed clinical proforma. Detail history with particular attention to age, clinical features, age at menarche, parity, obesity, history of contraceptives, history of hormone replacement therapy, history of diabetes, history of hypertension, history of estrogen producing ovarian tumor, age at menopause were taken.

Histopathological Examination

All specimens obtained either by endometrial curettage biopsy or hysterectomy were immersed in 10% formalin. The specimens were examined in the department of pathology, Dhaka Medical College with a particular emphasis on number, size, shape, color and consistency. This part was done by experienced pathologist in the department of Pathology of Dhaka Medical College. Tissue processing and staining: Routine tissue processing and Haematoxylin & Eosin staining were done at the Department of Pathology, Dhaka Medical College.

Microscopic Analysis

Following histopathological diagnoses were made according to WHO classification of endometrial hyperplasia: Simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia, Simple endometrial hyperplasia with atypia, Complex endometrial hyperplasia without atypia, Complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia.5

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses of the results were obtained by using window based computer software devised with Statistical Packages for Social Sciences (SPSS-16). Percentages were calculated to find out the proportion of the findings. The results were presented in Tables and Figures.

Results

Out of 70 histopathologically diagnosed endometrial hyperplasia cases, 53 cases were simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia, 8 cases were simple endometrial hyperplasia with atypia, 6 cases were complex endometrial hyperplasia without atypia and 3 cases were complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia. Majority of the patients 35(50%) were between 41-50 years of age (Table I).

Table I: Distribution of the study patients by Age (n=70)

| Age (Years) | SEH without atypia

(n=53) |

SEH with atypia

(n=8) |

CEH without atypia

(n=6) |

CEH with atypia

(n=3) |

Total

(n=70) |

|

| n | % | |||||

| 35-40 | 12 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 18 | 25.7 |

| 41-50 | 30 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 50.0 |

| 51-60 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 16 | 22.9 |

| 61-70 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| >70 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1.4 |

| Total | 53 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 70 | 100 |

(SEH without atypia- Simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia, SEH with atypia- Simple endometrial hyperplasia with atypia, CEH without atypia – Complex endometrial hyperplasia without atypia and CEH with atypia- Complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia)

Table II: Distribution of the study patients by menstrual history (n=70)

| Menstrual history | SEH without atypia

(n=53) |

SEH with atypia

(n=8) |

CEH without atypia

(n=6) |

CEH with atypia

(n=3) |

Total

(n=70) |

|

| n | % | |||||

| Irregular menstrual bleeding | 42 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 55 | 78.6 |

| Post-menopausal bleeding | 11 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 15 | 21.4 |

Majority of the patients (56 cases) achieved their menarche at 12-13 years of age in simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia and no patient achieved early menarche (before 10 years) (Table III)

Table III: Distribution of the study patients by age of menarche (n=70)

| Age of menarche (years) | SEH without atypia

(n=53) |

SEH with atypia

(n=8) |

CEH without atypia

(n=6) |

CEH with atypia

(n=3) |

Total

(n=70) |

|

| n | % | |||||

| 12-13 | 47 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 56 | 80.0 |

| 14-15 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 14 | 20.0 |

| Mean±SD | 13.7±0.7 | 13.8±1.3 | 13.3±1.0 | 12.7±0.6 | 13.6 | ±0.9 |

| Range (Min-max) | 12-15 | 12-15 | 12-15 | 12-13 | 12-15 | |

Out of 70 cases, 45(57.14%) were multipara. Among 45 cases, 36(51.4%) cases had 3 children, 6(8.6%) cases had 4 children and 3(4.3%) cases had 5 children (Table V).

By Basal Metabolic Index, obesity (BMI more than 30) was found in 34(48.6%) cases, among them 27 cases in simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia, 5 cases in simple endometrial hyperplasia with atypia and 2 cases in complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia (Table VI).

Table IV: Distribution of the study patients by age of menopause (n=70)

| Age of menopause | SEH without atypia

(n=53) |

SEH with atypia

(n=8) |

CEH without atypia

(n=6) |

CEH with atypia

(n=3) |

Total

(n=70) |

|

| n | % | |||||

| 50 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 26.6 |

| 51 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 33.3 |

| 52 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 40.0 |

| Mean±SD | 51.09±0.8 | 0±0 | 51.0±0 | 51.5±0.7 | 51.1 | ±0.8 |

| Range (Min-max) | 50-52 | 51-51 | 50-52 | 51-52 | 50-52 | |

Table V: Distribution of the study patients by parity (n=70)

| Para | SEH without atypia

(n=53) |

SEH with atypia

(n=8) |

CEH without atypia

(n=6) |

CEH with atypia

(n=3) |

Total

(n=70) |

|

| n | % | |||||

| 2 | 18 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 25 | 35.7 |

| 3 | 29 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 36 | 51.4 |

| 4 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 8.6 |

| 5 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4.3 |

| Mean±SD | 2.8±0.8 | 2.5±0.5 | 3.2±1.2 | 3.0±1.0 | 2.8±0.8 | |

| Range (Min-max) | 2-5 | 2-3 | 2-5 | 2-4 | 2-5 | |

Table VI: Distribution of the study patients by obesity by calculating Basal Metabolic Index (BMI) (n=70)

| Obesity by BMI (kg/m2) | SEH without atypia

(n=53) |

SEH with atypia

(n=8) |

CEH without atypia

(n=6) |

CEH with atypia

(n=3) |

Total

(n=70) |

|

| n | % | |||||

| Present | 27 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 34 | 48.6 |

| Absent | 26 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 36 | 51.4 |

Out of the total study cases, diabetes was found in 11 cases, hypertension was found in 24 cases, and history of associated estrogen producing tumor of ovary was found in 1 case (Table VII).

Table VII: Distribution of the study patients by diabetes, hypertension and history of associated estrogen producing tumour of ovary (n=70)

| Diseases | SEH without atypia

(n=53) |

SEH with atypia

(n=8) |

CEH without atypia

(n=6) |

CEH with atypia

(n=3) |

Total

(n=70) |

|

| n | % | |||||

| Diabetes | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 15.7 |

| Hypertension | 20 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 24 | 34.3 |

| History of associated estrogen producing tumour of ovary | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1.4 |

History of oral contraceptive pill was found in 15(21.4%) cases and history of hormone replacement therapy was found in 12(17.15%) cases (Table VIII).

Table VIII: Distribution of the study patients by history of Oral contraceptive pill (OCP) and history of Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) (n=70)

| History | SEH without atypia

(n=53) |

SEH with atypia

(n=8) |

CEH without atypia

(n=6) |

CEH with atypia

(n=3) |

Total

(n=70) |

|

| n | % | |||||

| H/O OCP | 7 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 15 | 21.4 |

| H/O HRT | 10 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 12 | 17.15 |

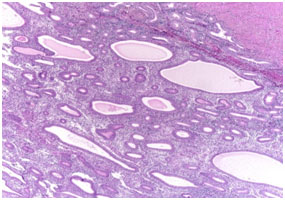

Figure 1. Photomicrograph showing simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia (H & E stain, x10)

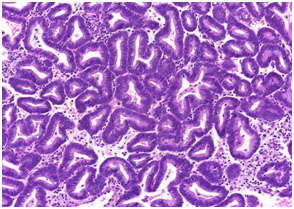

Figure 2. Photomicrograph showing simple endometrial hyperplasia with atypia (H & E stain, x40)

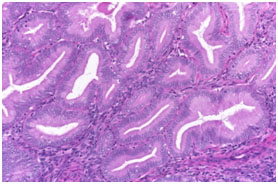

Figure 3. Photomicrograph showing complex endometrial hyperplasia without atypia(H & E stain, x40)

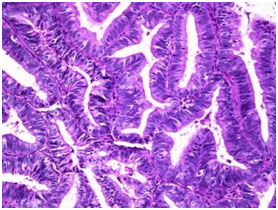

Figure 4. Photomicrograph showing complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia(H & E stain, x40)

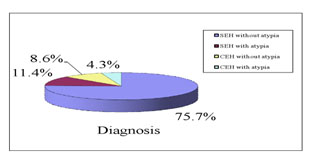

Microscopic pictures of different types of endometrial hyperplasia are shown in figures 1, 2,3 and 4. Pie chart showing the commonest diagnosis in 70 patients was SEH without atypia (75.7%) followed by SEH with atypia (11.4%; Fig-5).

Figure 5. Pie chart showing distribution of the patients by diagnosis (n=70)

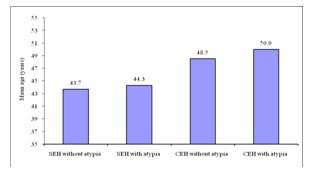

Figure 6. Bar diagram showing distribution of the patients according to mean age with diagnosis (n=70)

Discussion

Endometrial hyperplasia has a significant place in gynecological morbidity in women of reproductive age (10% to 18%).12 It is associated with menstrual irregularities and anaemia in women and poses a high risk for malignant transformation into endometrial cancer.13 Worldwide endometrial cancer is the most common gynecological cancer in peri and postmenopausal women.14,15 The incidence of endometrial adenocarcinoma not only has remained high but in recent years has tended to significantly increase in many countries, including Bangladesh.12,16

The diagnosis and classification of endometrial hyperplasia can be made by histopathological examination. The present cross-sectional study was carried out with an aim to observe the histopathological pattern of endometrial hyperplasia in peri and post-menopausal women. In the present study, the commonest diagnosed lesion was simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia which was 53(75.7%), followed by simple endometrial hyperplasia with atypia 8(11.4%), complex endometrial hyperplasia without atypia 6(8.6%) and then complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia 3(4.3%).

In this study it was observed that, the mean age was 43.7±7.9 years in simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia, 44.3±5.9 years in simple endometrial hyperplasia with atypia, 48.5±15.5 years in complex endometrial hyperplasia without atypia and 50.0±13.2 years in complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia. In our study, the age ranged from 35 to 75 years with a mean age of 45 years. The highest number of cases 35(50%) were in the fourth decade. These findings are almost similar to the studies carried out.17,13 In their study, they also found maximum cases in the fourth decade. However, the present study differed from the study conducted by Trimble et al.2 who reported the mean age as 58 years and the age range between 25 to 89 years. Probably this discrepancy is due to small number of cases in our study. The present study also differed from the study conducted.18 They observed that, the incidence of simple and complex hyperplasia without atypia were highest in women aged 50 to 54 years, whereas the rate of atypical hyperplasia was highest in women aged 60 to 64 years. This variation may be due to high expectancy of life in developed countries.

We observed, 55 cases were in their reproductive age and on menstrual history, all of them had irregular menstrual bleeding. Among 55 cases, majority (42) were diagnosed as simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypical, followed by (8) as simple endometrial hyperplasia with atypia. In this study it was observed that, 15 cases achieved menopause and postmenopausal bleeding. Out of 15 cases, on histopathological examination, 11 were diagnosed as simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia, 2 as complex endometrial hyperplasia without atypia and 2 as complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia. This finding is in concordance with that found in the study of Farquhar et al.19 Thus, it can be concluded that, postmenopausal bleeding does not always indicate a risk for development of endometrial carcinoma as simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia has only 1 to 3% risk for development of endometrial carcinoma.1

In the present study, postmenopausal patients were 15 in number. The mean age at which they achieved menopause was 51.09±0.8 years in simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia, 51.0±0 years in complex endometrial hyperplasia without atypia and 51.5±0.7 years in complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia. In this study it was observed that, most patients achieved menopause at the age of 52 years. This result is in concordance with the study done by Jetley et al.20 However, the number of menopausal patient is inadequate to come to any definite comment.

All the patients of this study were parous women. Parity causes estrogen-hormonal environment throughout the fertile years of a woman.9 In the present study it was found that, range of parity varied from 2 to 5 in all types of endometrial hyperplasia. This result is in concordance with the study done by Topcu et al.21,22

They also observed range of parity from 2 to 5 among the patients with endometrial hyperplasia. However, this finding has a pitfall of not having nullipara patient in the present study.

Obesity is a known risk factor for endometrial cancer. This excess risk is associated with the endocrine and inflammatory effects of adipose tissue. Adipocytes express aromatase that converts ovarian androgens into estrogens, which induce endometrial proliferation.10 In the present study, it was observed that by Body Mass Index (BMI), obesity (BMI more than 30) was found in 34 cases (48.6%). Among them, majority (27) cases were simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia. This result is in concordance with the study done by Epplein et al. 23,21,17 they also found 48.89% cases of endometrial hyperplasia in obese women.

In this study. it was observed that diabetes was found in 11 cases (15.7%). Similar study was done by Bera et al.17 They also found association of diabetes mellitus in 18 cases (15%) of endometrial hyperplasia.

In present study it was observed that, hypertension was found in 24 cases (34.3%). This result is in concordance with the study done by Bera et al.17 They also found 36 cases (35%) of endometrial hyperplasia in hypertensive patients. It is observed that, in the present study and other comparable studies, endometrial hyperplasia is found in diabetic and hypertensive patient, but whether this association is statistically significant or not or whether it carries a risk of endometrial carcinoma for diabetic and hypertensive women need to be ascertained with a large series of study population.

The history of associated estrogen producing tumor of ovary was found in 1 case and it was a case of complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia. Though this number is very insignificant in our study, Gregory et al.24 have shown in their study that, women with ovarian tumor and polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) have a higher risk of development of estrogen-induced endometrial hyperplasia and cancer.

We observed that history of OCP in 15 cases. Out of 15 cases, 7 cases were simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia, 4 cases were simple endometrial hyperplasia with atypia, 3 cases were complex endometrial hyperplasia without atypia and 1 case was complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia. Epplein et al.23 also the found association of OCP in 18 cases of endometrial hyperplasia in the women of reproductive age.

History of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was found in 12 cases and majority (10) were simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia. Epplein et al.23 have found similar association with HRT which is composed of estrogen only.

In the present study, no patient gave family history of endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial carcinoma. This may be due to unawareness of the study patients about their family history. Other studies also found no association with the family history of endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial carcinoma, though they were aware about their family history.17, 23

Limitation of the Study

Our study included few numbers of postmenopausal women. It was a cross-sectional study. To evaluate the risk factors for endometrial hyperplasia and the risk of endometrial hyperplasia to progress to endometrial carcinoma, ideally a cohort or follow-up study should be done.

Conclusion

We found that most of the patients were in the fourth decade and all the patients had chief complaints of either irregular menstrual bleeding or postmenopausal bleeding. On USG, all of them had bulky uterus and all the patients were parous women. We found no significant association with obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, oral contraceptive pill or estrogen producing ovarian tumour but significant association was found with HRT in postmenopausal women. None of the patient had family history of endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial carcinoma.

Recommendations

A large follow–up study is recommended for patients of endometrial hyperplasia selected for conservative treatment with progestogen and GnRH-agonists. Monitoring should be done by observing the Ki-67 expression in these patients. If the Ki-67 expression increases, they should be treated by surgical intervention.

References

- Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic basis of disease, Professional edition e-book. elsevier health sciences; 2014 Aug 27.

- Trimble CL, Kauderer J, Zaino R, Silverberg S, Lim PC, Burke JJ, Alberts D, Curtin J. Concurrent endometrial carcinoma in women with a biopsy diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Cancer, 2006; 106(4):812-9.

- Buckley CH. Fox H, Biopsy pathology of the endometrium. 2nd London Arnold, 2002 pp.209-240.

- Kurman RJ, Norris HJ. Evaluation of criteria for distinguishing atypical endometrial hyperplasia from well differentiated carcinoma. Cancer, 1982; 49(12):2547-59.

- Rosai J. Rosai and Ackerman’s surgical pathology e-book. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011 Jun 20.

- Rakha E, Wong SC, Soomro I, Chaudry Z, Sharma A, Deen S, Chan S, Abu J, Nunns D, Williamson K, McGregor A. Clinical outcome of atypical endometrial hyperplasia diagnosed on an endometrial biopsy: institutional experience and review of literature. The American journal of surgical pathology, 2012; 36(11):1683-90.

- Pungal A, Balan R, Cotuţiu C. Hormone receptors and markers in endometrial hyperplasia. Immunohistochemical study. Revista medico-chirurgicala a Societatii de Medici si Naturalisti din Iasi, 2010; 114(1):180-4.

- Lacey JV, Chia VM. Endometrial hyperplasia and the risk of progression to carcinoma. Maturitas, 2009; 63(1):39-44.

- Bayo S, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S, Munoz N, Combita AL, Coursaget P, Diaz M, Dolo A, van den Brule AJ, Meijer CJ. Risk factors of invasive cervical cancer in Mali. International journal of epidemiology, 2002; 31(1):202-9.

- Schmandt RE, Iglesias DA, Lu KH. Understanding obesity and endometrial cancer risk: opportunities for prevention. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2011; 205(6):518-25.

- Fabjani G, Kucera E, Schuster E, Minai-Pour M, Czerwenka K, Sliutz G, Leodolter S, Reiner A, Zeillinger R. Genetic alterations in endometrial hyperplasia and cancer. Cancer letters, 2002; 175(2):205-11.

- Benyuk VA, Kurochka VV, Vynyarskyi YM, Goncharenko VM. Diagnostic algorithm endometrial pathology using hysteroscopy in reproductive age women. Women Health (ZdorovyaZhinky), 2009; 6(42):54-6.

- Goncharenko VM, Beniuk VA, Kalenska OV, Demchenko OM, Spivak MY, Bubnov RV. Predictive diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia and personalized therapeutic strategy in women of fertile age. EPMA Journal, 2013; 4(1):24.

- Nicolaije KA, Ezendam NP, Vos MC, Boll D, Pijnenborg JM, Kruitwagen RF, Lybeert ML, van de Poll-Franse LV. Follow-up practice in endometrial cancer and the association with patient and hospital characteristics: a study from the population-based PROFILES registry. Gynecologic oncology, 2013; 129(2):324-31.

- Giordano G, Gnetti L, Merisio C, Melpignano M. Postmenopausal status, hypertension and obesity as risk factors for malignant transformation in endometrial polyps. Maturitas, 2007; 56(2):190-7.

- Zaporozhan VN, Tatarchuk TF, Dubinina VG, Kosey NV, Diagnosis and treatment of endometrial hyperplastic processes. Reprod Endocrinol, 2012; 1(3):5-12.

- Bera H, Mukhopadhyay S, Mondal T, Dewan K, Mondal A, Sinha SK. Clinicopathological study of endometrium in peri and postmenopausal women in a tertiary care hospital in Eastern India. OSR-JDMS, 2014; 13:16-23.

- Giuntoli RL, Zacur HA, Goff B, Garcia RL, Falk SJ. Classification and diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia. Offical Reprint from UpToDate. 2014 Jun.

- Farquhar CM, Lethaby A, Sowter M, Verry J, Baranyai J. An evaluation of risk factors for endometrial hyperplasia in premenopausal women with abnormal menstrual bleeding. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 1999; 181(3):525-9.

- Jetley S, Rana S, Jairajpuri ZS. Morphological spectrum of endometrial pathology in middle-aged women with atypical uterine bleeding: A study of 219 cases. Journal of mid-life health, 2013;4(4):216.

- Topcu HO, Erkaya S, Guzel AI, Kokanali MK, Sarıkaya E, Muftuoglu KH, Doganay M. Risk factors for endometrial hyperplasia concomitant endometrial polyps in pre-and post-menopausal women. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 2014; 15(15):5423-5425.

- Kudesia R, Singer T, Caputo TA, Holcomb KM, Kligman I, Rosenwaks Z, Gupta D. Reproductive and oncologic outcomes after progestin therapy for endometrial complex atypical hyperplasia or carcinoma. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2014; 210(3):255-261.

- Epplein M, Reed SD, Voigt LF, Newton KM, Holt VL, Weiss NS. Risk of complex and atypical endometrial hyperplasia in relation to anthropometric measures and reproductive history. American journal of epidemiology, 2008; 168(6):563-70.

- Gregory CW, Wilson EM, Apparao KB, Lininger RA, Meyer WR, Kowalik A, Fritz MA, Lessey BA. Steroid receptor coactivator expression throughout the menstrual cycle in normal and abnormal endometrium. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2002; 87(6):2960-6.